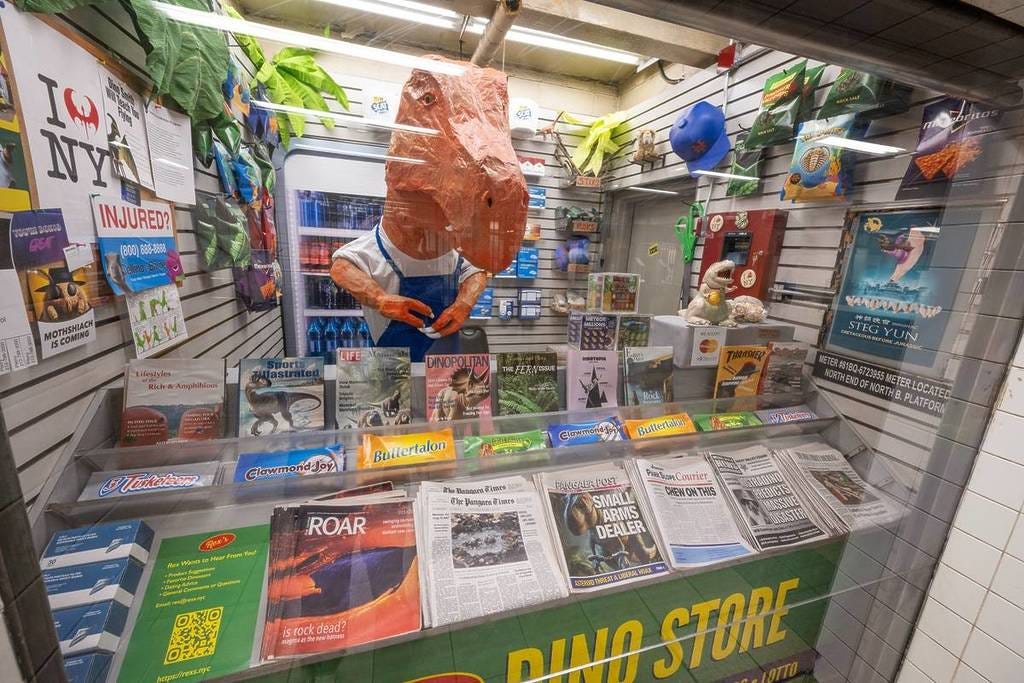

At the Grand Army Plaza subway station, you’ll find Rex’s Dino Store tucked inside a long-vacant kiosk. Behind the counter, Rex—the papier-mâché T. rex namesake—is slinging prehistoric essentials like Sportszillastrated, Meteoritos, and Snarlboro Reds. The tongue-in-cheek installation, dreamed up by artists Akiva Leffert and Sarah Cassidy, has transformed a forgotten corner of the station into a playful, community-centered destination that’s drawn thousands of curious commuters.

Launched in 2023, the MTA’s Vacant Unit Activation Program was designed to turn empty retail spaces into small art installations, giving passengers a light and playful reprieve from the otherwise hectic morning commute. It’s a reminder that subway stations aren’t just infrastructure—they’re part of our neighborhoods, our routines, our third spaces. Behind the grime and monotony, they’re deeply woven into the fabric of daily life. This program is a great start, but it’s limited. Two years in, there are just 12 installations across 472 stations. If one isn’t in your orbit, you’d never know it existed.

The bigger question is: what else can the MTA do to make stations feel like real third spaces? VUAP was born out of necessity—to fill vacant storefronts—but the MTA’s real estate portfolio is massive. From streetside kiosks to abandoned mezzanines, there’s untapped potential everywhere. The VAUP acknowledges that maybe we don’t need another coffee shop (there are five on my daily commute, not including half a dozen street carts), but that doesn’t mean these spaces cant be utilized. What if these spaces were offered to small businesses on short-term leases, or handed over to local artists? Stations like Times Square, West Fourth, and 57th Street have mezzanines the size of small plazas. What would it look like to treat them like public squares instead of leftover space? The Turnstyle Underground Market at 59th and Columbus Circle has proven the format for nearly a decade offering concessions and shoping. At a time when the MTA is strapped for funding this can also serve as another diverse revenue source.

There’s also something to be said for the broken windows theory here. When stations feel cared for—clean, well-lit, thoughtfully designed—they’re not just nicer to pass through, they’re treated with more respect. Fare evasion drops, safety improves, and people start to see the subway as part of their community rather than something to endure. That’s why in a past post, Hayden Clarkin and I explored what it would take to make the subway beautiful—not just functional, but dignified. When we invest in the aesthetics and upkeep of these spaces, we’re not just polishing tiles, we’re signaling that these places matter. And when they matter, they become fertile ground for small businesses, pop-up concessions, and local vendors to thrive.

The subway is already an integral part of life for millions of New Yorkers. It’s where we wait, rush, pause, and sometimes reflect. If we’re serious about treating it as a third space, we need to go beyond pilot programs and rethink the entire experience—from the mezzanine to the platform. Because when a space feels like it belongs to the community, the community shows up for it.

I think about this often in the context of Grand Central Madison. It's aesthetically pleasing, but severely lacking in proper concessions and retail—especially when compared to Penn Station or the lower level of Grand Central Terminal. It’s been over two and a half years since it opened, and so far there are just a few small snack carts and an oyster bar still in progress.

Love this Aaron, every time I pass through W 4th St station I think what a shame it is that the entire mezzanine space between the lines is just sitting there empty! Even if we can't get vendors or concessions set up in that space, bringing in some art to liven it up would be a massive improvement over the current liminal space vibe it has.

I'm also curious what you think of Mamdani's proposal to use the vacant spaces in some subway stations as crisis hubs to serve the homeless. On one hand, it seems great to provide supportive infrastructure for these populations right where they are, but on the other, it risks making the stations an even less appealing place to spend time in.